What makes a Tourniquet both Safe and Effective?

How Do You Know If a Tourniquet Is Working Safely and Effectively?

By Hannah Herbst, Inventor of AutoTQ®

One of the most common questions I hear when people learn about tourniquets is:

“How do I know if a tourniquet is actually stopping the bleeding—and doing it safely?”

It’s an important question. Tourniquets save lives, but only when they are applied correctly and at the right pressure. Understanding how tourniquet pressure works—and why cuff width matters—can help demystify bleeding control and build confidence in emergency response, whether in civilian, prehospital, or military settings.

What Is a Tourniquet?

A tourniquet is a compression device that has been used in medicine and trauma care for more than 2,000 years. It is placed proximal to a site of severe extremity bleeding and applies circumferential pressure around the limb to compress arteries and veins, temporarily stopping blood flow.

Tourniquet pressure is measured the same way your doctor measures blood pressure: millimeters of mercury (mmHg). This unit reflects how much pressure is being applied to the limb surface to occlude arterial flow.

In other words, mmHg is a measure of how tightly the tourniquet is squeezing the limb.

The Two Main Types of Tourniquets

Windlass Tourniquets

Windlass tourniquets are tightened manually. The user places the device above the bleeding site and twists a rigid rod (the “windlass”) until bleeding appears to stop.

Key characteristics:

Typically 2 inches wide or narrower

Considered narrow tourniquets

Applied pressure varies significantly depending on the user

High risk of over- or under-tightening

Numerous studies have shown that manual tourniquets can generate very high localized pressures and steep pressure gradients, particularly when narrow cuffs are used (McEwen & Casey, 2009; Wall et al., 2013).

2. Pneumatic Tourniquets

Pneumatic tourniquets use air pressure, similar to a blood pressure cuff. Air is inflated into a cuff until arterial blood flow is occluded.

Key characteristics:

Pressure may be preset or adjusted

Typically use wider cuffs

Can achieve arterial occlusion at lower pressures

Widely used in surgical and clinical environments

Adaptive pneumatic systems have been shown to achieve effective occlusion while minimizing unnecessary pressure, reducing pain and nerve compression risk (Liu et al., 2013; Pedowitz et al., 1993).

Both windlass and pneumatic tourniquets have advantages and limitations—but when it comes to safety, pressure control matters more than most people realize.

Why Tourniquet Pressure Matters

Decades of research have demonstrated a consistent and well-documented relationship:

The narrower the tourniquet cuff, the higher the pressure required to stop bleeding.

The wider the cuff, the lower the pressure required to achieve arterial occlusion.

This relationship has been demonstrated repeatedly across surgical, biomechanical, and trauma literature (Crenshaw et al., 1988; Graham et al., 1993; Masri et al., 2020).

Excessively high tourniquet pressure—particularly from narrow cuffs—has been associated with:

Nerve compression injuries

Increased pain

Tissue ischemia

Complications below the tourniquet line

(Ochoa et al., 1972; Masri, 2020; Kovar et al., 2015)

This is one reason tourniquets historically developed a negative reputation. Importantly, the risk is not inherent to tourniquet use itself, but rather to high pressure gradients and poorly controlled application (Wall et al., 2013; Masri et al., 2020).

What the Research Shows

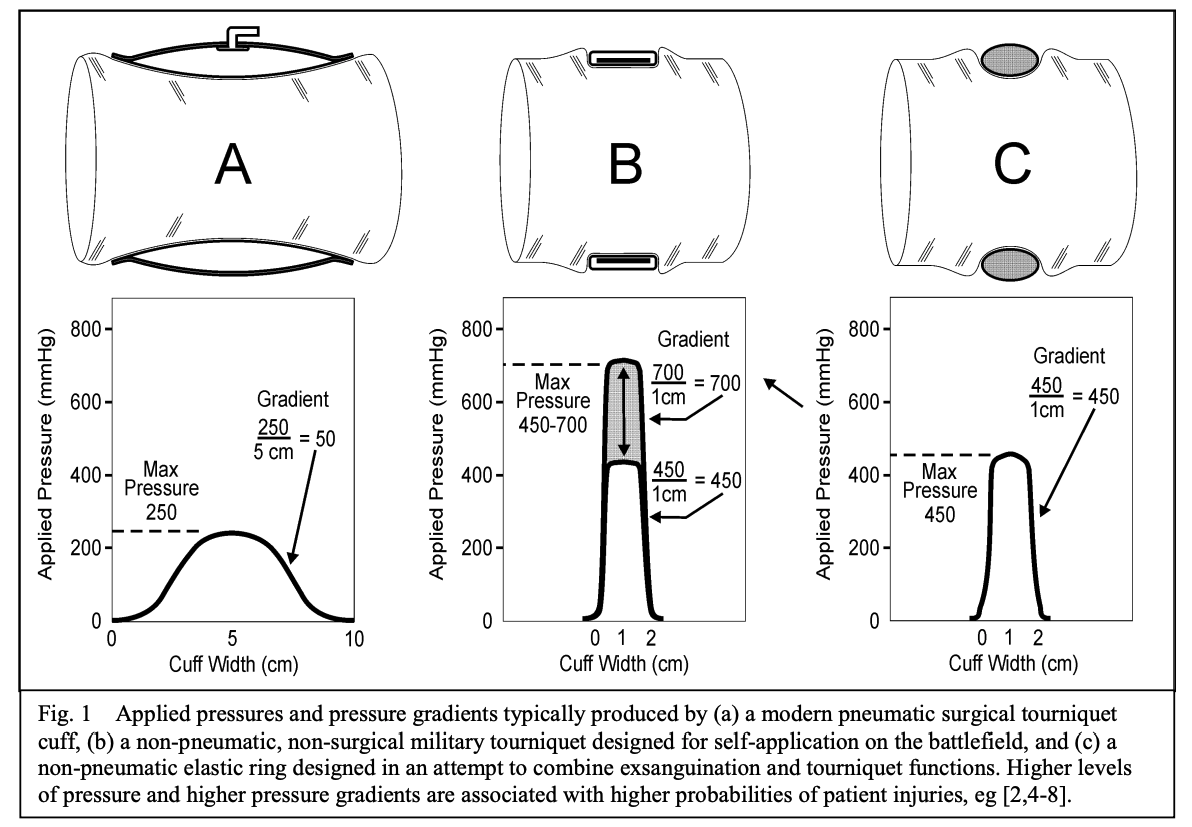

McEwen and Casey’s foundational work demonstrated that non-pneumatic, narrow tourniquets generate hazardous pressure gradients, while pneumatic tourniquets with wider cuffs distribute pressure more evenly across the limb (McEwen & Casey, 2009).

Image credit: J. McEwen and V. Casey, “Measurement of Hazardous Pressure Levels and Gradients Produced on Human Limbs by Non-Pneumatic Tourniquets”, CMBES Proc., vol. 32, no. 1, May 2009.

Subsequent studies confirmed that wide cuffs can occlude arterial flow at subsystolic pressures, reducing the need for excessive compression (Graham et al., 1993). Clinical and volunteer studies further showed that wide tourniquets produce less pain and nerve compression than narrow cuffs, even when achieving the same occlusive effect (Kovar et al., 2015).

Masri and colleagues reviewed decades of evidence and concluded that tourniquet-induced nerve injuries are driven by high pressure levels and steep gradients, not simply by duration of use (Masri et al., 2020). These findings are echoed in military and prehospital literature emphasizing controlled pressure application to reduce morbidity (Wall et al., 2013; Wall et al., 2021).

Modern trauma and combat casualty data reinforce that properly applied tourniquets are life-saving and not associated with increased limb loss, even in severe injuries, when pressure and duration are managed appropriately (Kragh et al., 2011; Kauvar et al., 2018).

Taken together, the evidence supports a clear conclusion:

Tourniquet safety depends on cuff width, pressure control, and application technique—not brute force.

How AutoTQ Was Designed Differently

When we began developing AutoTQ®, our goal was to combine:

The ruggedness and rapid deployment of emergency tourniquets

The precision and pressure control of pneumatic systems used in medicine

Throughout development, we collaborated with physicians, paramedics, nurses, and tourniquet researchers—many of whom routinely apply tourniquets in surgical, prehospital, and trauma settings.

The guidance was consistent:

Use a wide cuff. Control the pressure. Avoid unnecessary force.

AutoTQ’s cuff widths reflect this evidence-based approach:

Arm cuff: 3 inches (7.62 cm)

Leg cuff: nearly 4 inches (10.16 cm)

These dimensions align with research demonstrating that wider cuffs reduce minimum effective pressure while maintaining reliable arterial occlusion (Crenshaw et al., 1988; Graham et al., 1993; Pedowitz et al., 1993).

How AutoTQ Controls Pressure

AutoTQ uses a stepped pneumatic inflation approach designed to achieve occlusion without overshooting.

Initial inflation: 300 mmHg

Sufficient to stop bleeding in most adults

Maximum inflation: 600 mmHg

Allows escalation if needed without default over-compression

This approach reflects principles used in adaptive pneumatic tourniquet systems shown to reduce unnecessary pressure while maintaining occlusion (Liu et al., 2013).

“It Feels Like a Blood Pressure Cuff—Is It Really Working?”

When EMS professionals, medics, or military personnel try AutoTQ on themselves for the first time, the most common reaction is surprise—followed by the question:

“Is it really stopping my blood flow?”

This reaction highlights an important physiological truth:

All blood pressure cuffs briefly function as tourniquets.

When blood pressure is measured, the cuff inflates until arterial flow stops, then deflates until flow returns. This same principle is used clinically to determine safe pneumatic tourniquet pressures during surgery (Pedowitz et al., 1993). Watch this video to see how it works (starting at ~3:40)

Effective tourniquet pressure does not require crushing the limb—it only requires enough circumferential pressure to stop arterial flow.

How We Verify Effectiveness: Doppler Testing

To confirm arterial occlusion, Doppler ultrasound is used—an industry standard for tourniquet evaluation on human limbs (Barron et al., 2017).

Doppler probes are placed distal to the tourniquet:

Brachial artery (arm)

Popliteal artery (leg)

Before inflation, arterial pulsation is visible and audible. After inflation, the Doppler signal disappears, confirming occlusion.

In testing, arterial occlusion typically occurs at or below 300 mmHg, consistent with literature on wide-cuff pneumatic systems (Graham et al., 1993; Liu et al., 2013).

From Idea to Real-World Impact

Four years ago, AutoTQ began as an idea to make bleeding control simpler, safer, and more consistent.

Today, it reflects decades of tourniquet science, trauma research, and real-world feedback—supporting a growing body of evidence that thoughtful pressure control saves lives while reducing risk (Kragh et al., 2011; Berry et al., 2023).

Learn More

You can review our research and testing methodology at:

👉 theautotq.com/occlusion

Thank you for reading! Want to get in touch with our team? Reach out here.

References

Barron, M. R., et al. (2017). Smartphone-based mobile thermal imaging technology to assess limb perfusion and tourniquet effectiveness under normal and blackout conditions. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 83(6), 1129–1135.

Berry, C., et al. (2023). Prehospital hemorrhage control and treatment by clinicians: A joint position statement. Prehospital Emergency Care, 27(5), 544–551.

Crenshaw, A. G., et al. (1988). Wide tourniquet cuffs more effective at lower inflation pressures. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 59(4).

Graham, B., Breault, M. J., McEwen, J. A., & McGraw, R. W. (1993). Occlusion of arterial flow in the extremities at subsystolic pressures through the use of wide tourniquet cuffs. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 286, 257–261.

Kauvar, D. S., Miller, D., & Walters, T. J. (2018). Tourniquet use is not associated with limb loss following military lower extremity arterial trauma. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 85(3), 495–499.

Kovar, F. M., et al. (2015). Nerve compression and pain in human volunteers with narrow vs wide tourniquets. World Journal of Orthopedics, 6(4), 394–399.

Kragh, J. F., Jr., et al. (2011). Battle casualty survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop limb bleeding. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 41(6), 590–597.

Kragh, J. F., Jr., et al. (2011). Minor morbidity with emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding in severe limb trauma: Research, history, and reconciling advocates and abolitionists. Military Medicine, 176(7), 817–823.

Liu, H., et al. (2013). Development of adaptive pneumatic tourniquet systems based on minimal inflation pressure for upper limb surgeries. BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 12, 92.

Masri, B. A., Eisen, A., Duncan, C. P., & McEwen, J. A. (2020). Tourniquet-induced nerve compression injuries are caused by high pressure levels and gradients: A review of the evidence to guide safe surgical, pre-hospital and blood flow restriction usage. BMC Biomedical Engineering, 2.

Masri, B. A. (2020). Tourniquet-induced nerve compression injuries and related complications. BioMed Central Biomedical Engineering.

McEwen, J. A., & Casey, V. (2009). Measurement of hazardous pressure levels and gradients produced on human limbs by non-pneumatic tourniquets. Proceedings of the Canadian Medical and Biological Engineering Society (CMBES), 32(1).

Ochoa, J., et al. (1972). Anatomical changes in peripheral nerves compressed by a pneumatic tourniquet. Journal of Anatomy, 113(3).

Pedowitz, R. A., et al. (1993). The use of lower tourniquet inflation pressures in extremity surgery facilitated by curved and wide tourniquets and an integrated cuff inflation system. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 287, 237–244.

Wall, P. L., et al. (2013). Tourniquets and occlusion: The pressure of design. Military Medicine, 178(5), 578–587.

Wall, P. L., Hingtgen, E., & Buising, C. M. (2021). Pressure responses of tourniquet practice models to calibrated force applications. Journal of Special Operations Medicine, 21(2), 11–17.